Let’s start with an assumption:

We want to live meaningful lives on a healthy planet and we want the generations to come to be able to do the same.

And a related definition of true sustainability (Ehrenfeld 2009):

[Sustainability is] the possibility that humans and other life will flourish on the planet forever

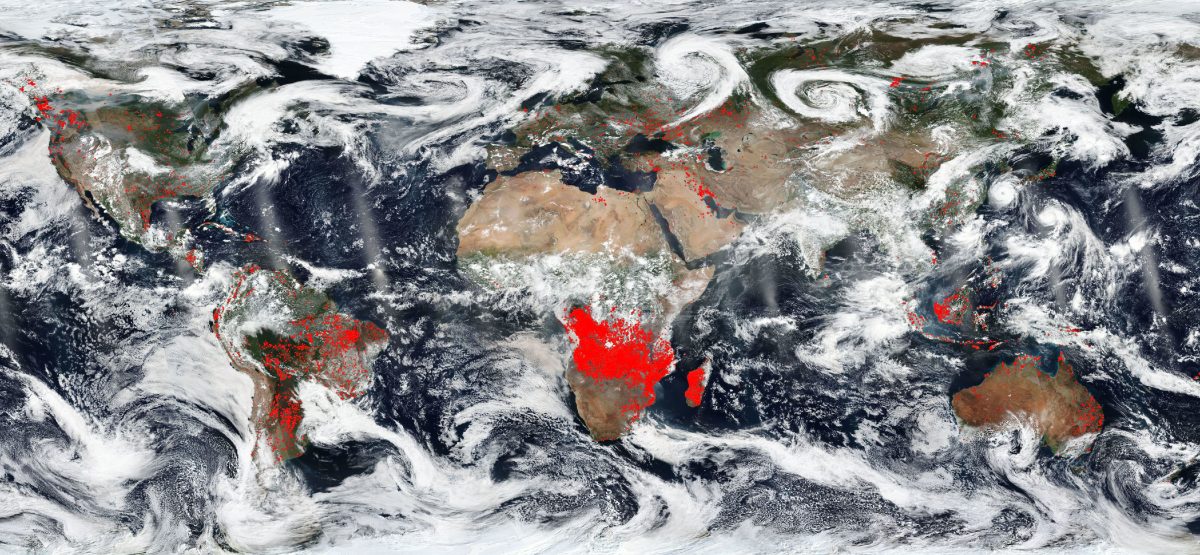

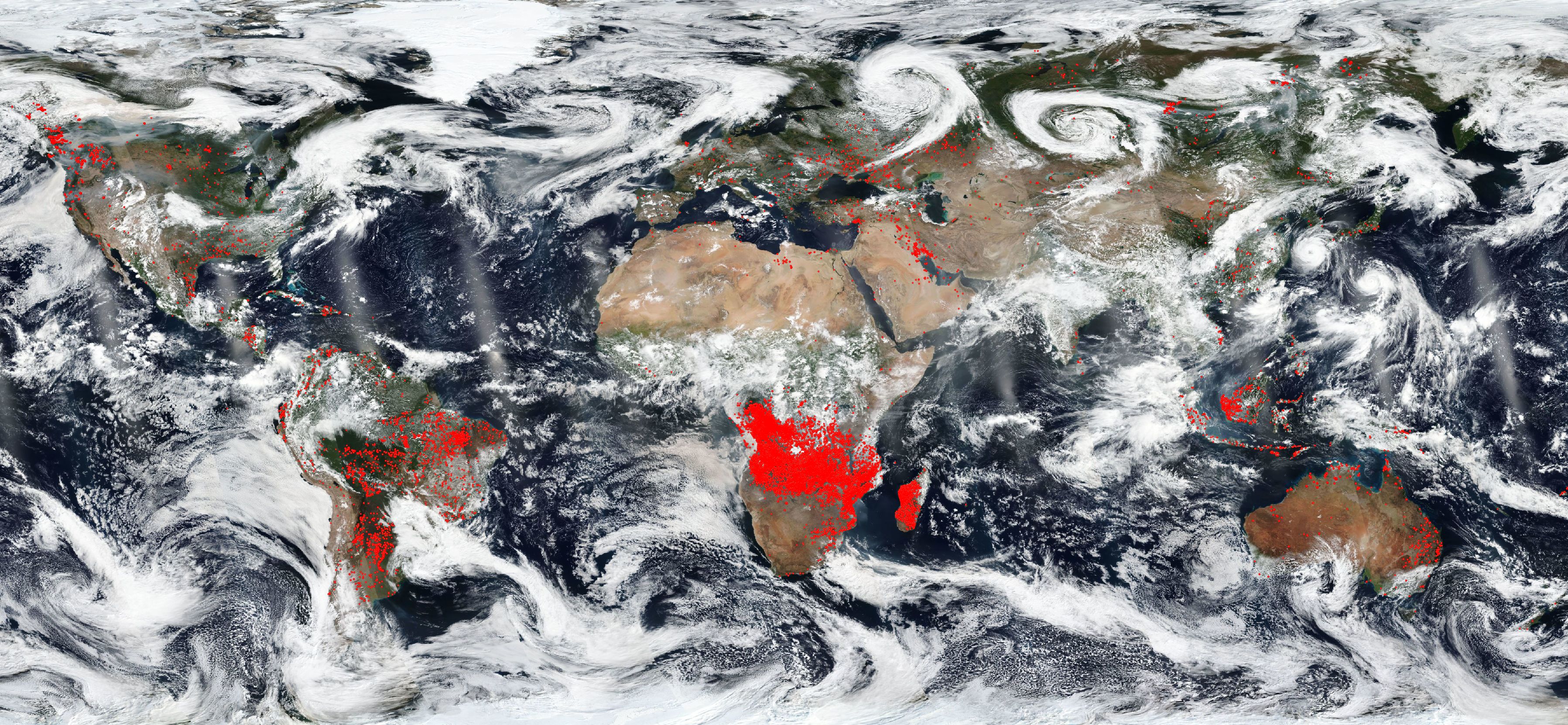

We are currently using 1.7 Earths each year. This means that ‘we use more ecological resources and services than nature can regenerate, through overfishing, overharvesting forests, and emitting more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere than ecosystems can absorb’ (source).

Our current way of life is deeply unsustainable.

Table of Contents

A realisation

Bad news fills our feeds every day. In part this is because bad news gets more reactions out of us than good news. However, a large proportion of the bad news is true. Things really are getting worse – especially for someone else, somewhere else, out of our immediate sight.

Climate breakdown, environmental degradation, inequality, undernutrition, ill health, poverty, powerlessness, dispossession, detachment, addiction. For a long time, I have been grappling with understanding these seemingly separate trends. I’ve been unable to work out why they all are happening, and what could be done to address them, all the while enjoying my privileged position in the world. Turns out I have been focusing on the individual symptoms without looking at the big picture – the system that ties them all together.

The root cause

I recently read Raj Patel’s and Jason W. Moore’s 2018 book ‘A History of the World in Seven Cheap Things: A Guide to Capitalism, Nature, and the Future of the Planet’ and it was a revelation. It is a very compelling account that draws together many different threads throughout history to point to one thing: capitalism. A quote:

If capitalism is a disease, then it’s one that eats your flesh—and then profits from selling your bones for fertilizer, and then invests that profit to reap the cane harvest, and then sells that harvest to tourists who pay to visit your headstone.61 But even this description isn’t adequate. The frontier works only through connection, fixing its failures by siphoning life from elsewhere. A frontier is a site where crises encourage new strategies for profit.

You can read the complete introduction to the book here (pdf).

Capitalism and its inherent profit motive mean that the buyers and sellers in the system are always looking for cheaper ways to do things, forever driving down prices. That is how us, who are privileged, have gotten to the standard of living we currently enjoy.

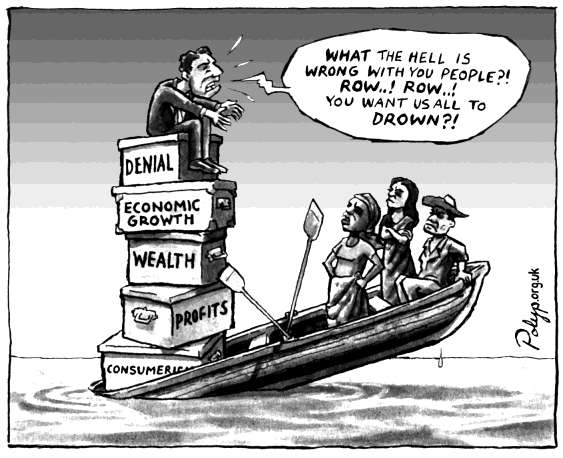

To keep going on the trajectory of infinite growth, something and someone is always being exploited. Capitalism can only exist through new frontiers, new innovative forms of extraction. It’s a winner-takes-all pyramid scheme with an expiry date in the near future.

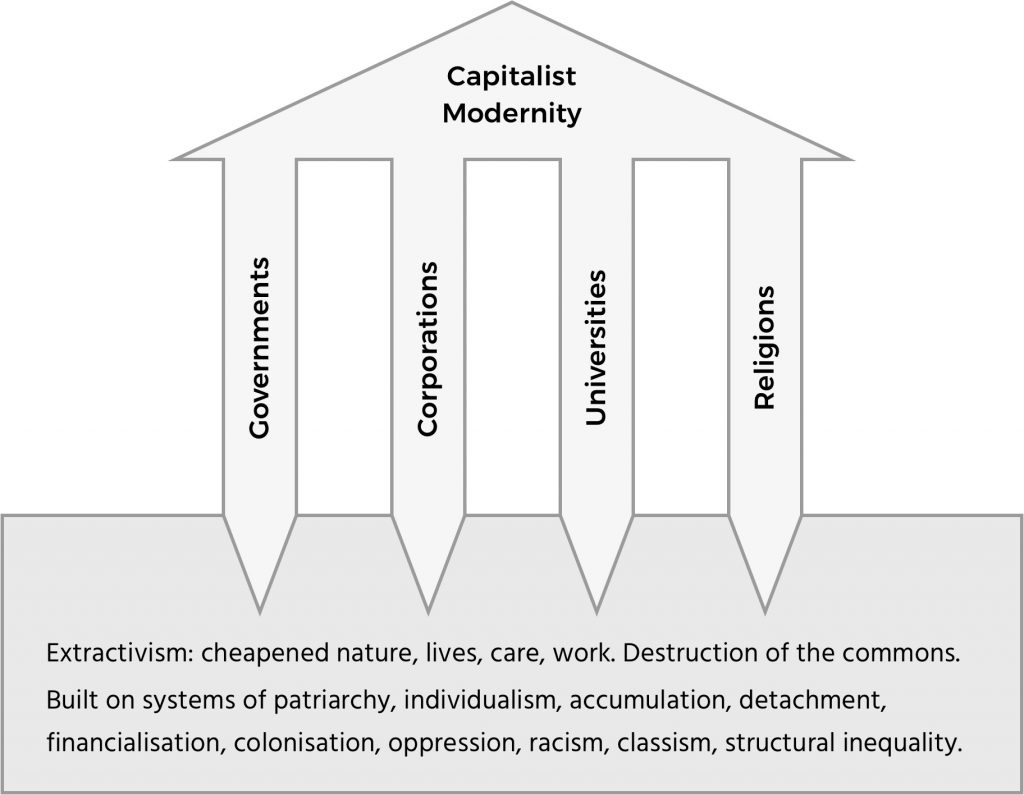

Defuturing institutional structures

Capitalism does not operate in isolation but relies on many other systems and structures: corporations, the state, technology, universities, even religion. All of these systems and structures work in unison to form an apparatus that maintains the status quo; an apparatus that won’t allow us to deviate from the path that we are forced to travel on.

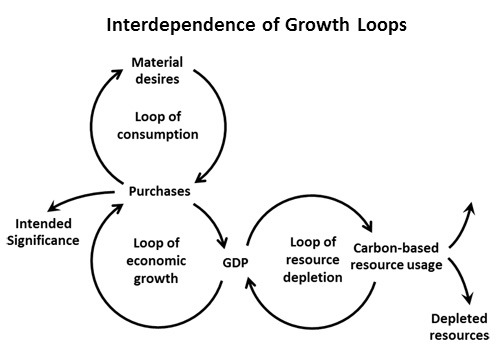

Infinite growth on a finite planet

Our planet Earth is finite. Infinite economic growth married to infinite material growth is physically impossible. Today, we are not living anywhere near within the constraints of the planet. Many of us have trouble even seeing, let alone acknowledging these constraints: we are currently consuming 1.7 Earths per year, soon predicted to grow to 2-3 Earths.

We believe in the mantra of economic growth as if it was the only form of growth that mattered, to the extent that we will not allow economic growth to be questioned or sacrificed for anything else – even when that growth is destroying our future, and the futures of others.

Fish cannot see the water that they live in; it is as if it did not exist. Similarly, we cannot see the system of capitalism that we are trapped in – it is just what ‘the world’ is like to us. In order to see the system, you need an intervention, a momentary interruption that allows you to rise above modernity and see it for what it really is. For me, reading Patel & Moore’s book was that intervention.

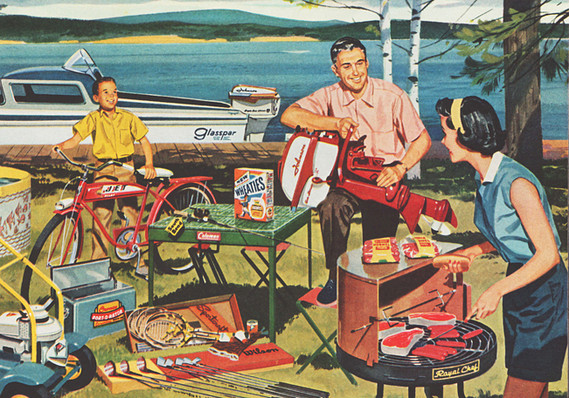

Contrary to popular belief, we cannot have it all

The narrative of western culture promotes the idea that we can have it all, and more. If you just stick to the preconceived pathway there is no limit to how many things you can accumulate, how many places you can visit, how many experiences you can have. More is always better.

This is not true. The lifestyle that we have today is stolen.

It is stolen from the First Nations people of Australia – including the Wurundjeri people on whose land I write this very piece. It is stolen from the beings – human and extra-human – that have depended for generations on the forests that are logged to provide us with our convenient flat-packed furniture.

Indeed, our lifestyle is stolen from all oppressed, colonised, and exploited peoples around the world, all ecosystems that are destroyed and mined for profit, and from the children of our children whose futures we are denying by not confronting capitalism today.

Through excess production and consumption, capitalism actively engages in defuturing – erasing potential futures.

Here’s what we need to do

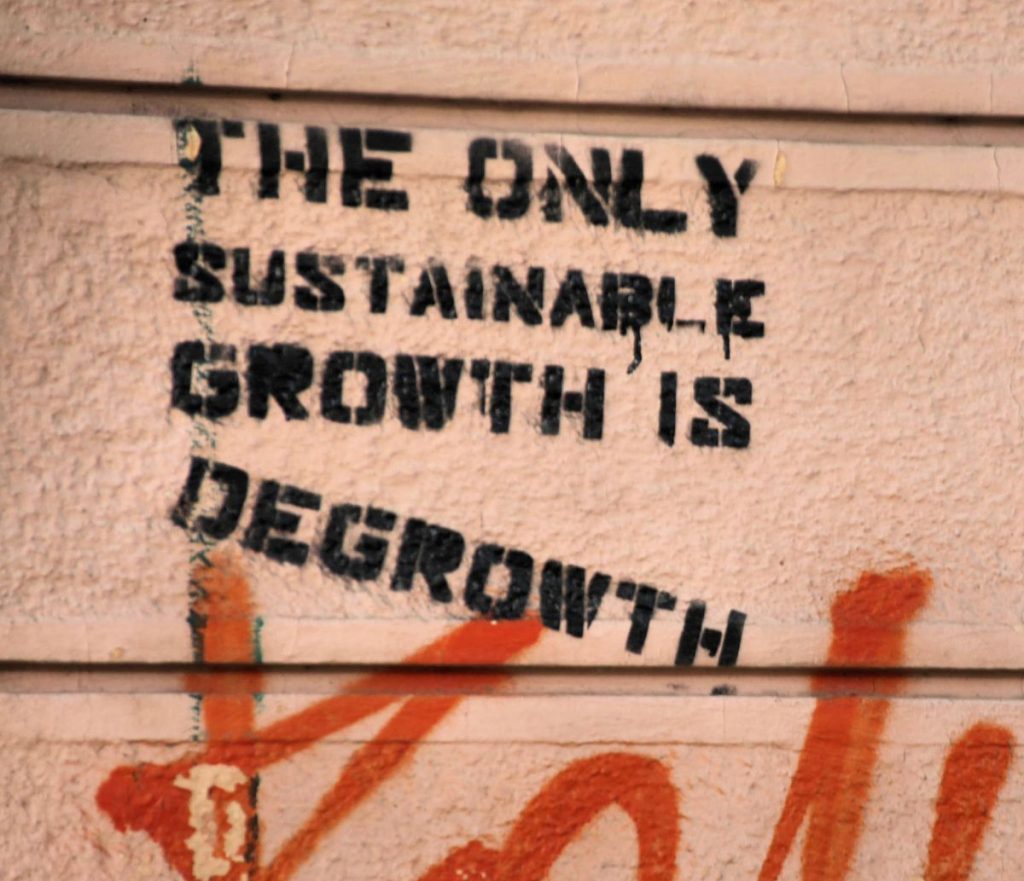

As the privileged, what we need is degrowth – we need to stop mistaking material growth for progress. We need to redefine what progress means at every level, and move away from the current globalised capitalist economy-centred models.

We are accustomed to the flawed idea that subsequent generations will always have more material goods than the preceding ones. This model is broken.

We have lived in the age of entitlement for long enough. We are programmed by the system to be the kids in the toy store, pointing at every aisle, wanting one thing after another, never satisfied. Open up pretty much any online store homepage or Instagram influencer feed today: we need none of those things, we are just being manipulated to want them. We have to understand that we cannot have all the things.

Here are some examples of what this means in practice, for you and me, not next decade but right now:

- We need to stop buying stuff that we don’t need

- We need to stop flying for leisure

- We need to stop driving for fun

- We need to stop buying fast food, fast fashion, fast anything

- We need to stop being distracted by the hollow promises of ‘green’, ‘eco’ and ‘sustainable’, as they are commonly defined

- We need to stop buying global and go local instead

- We need to stop consuming media and entertainment keeping us hooked

- We need to stop fetishising technology

- We need to stop working jobs that permeate the system

- We need to shift our focus from paid work to local work that helps our families and communities

- We need to stop ignoring what is right in front of us.

Equally important to changing our own behaviour, we must make our institutions change too: corporations, governments and universities. And if our institutions will not change, we must replace them.

To undo capitalism means to rethink everything. In short, we need to unlearn our current worldview and collectively re-imagine alternatives that are actually sustainable. Also, we need to envision futures that are good for all nature and people, not just a few.

Endless obstacles

For most privileged people, none of my suggestions above are going to sit well. It will sound like a preachy invasion from someone who has no right to tell others what to do – which is absolutely true. Furthermore, whilst I’m heeding some of my own advice above, I’m not living nearly within these constraints myself. My life is unsustainable at present, as are the lives of many around me.

It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his income depends on his not understanding it. –Upton Sinclair

The system we are part of has been built over centuries, and it is encoded into our existence and institutions in innumerable ways. The sheer scale of the change required appears insurmountable.

Who’s driving change

Our situation is extremely serious but it is not all despair and hopelessness. There are pockets of light in the form of grassroots initiatives all around the world:

- The Degrowth movement

- The Permaculture movement

- The Transition Network

- The Simplicity Institute and the Sufficiency movement

- The Decolonisation movements

- The commoning movement

These movements and initiatives approach the systemic problems from different angles, and it is great to see so many of them pop up in so many locations. I strongly encourage you to investigate and engage with one or more of these in your local area.

It may not work but at least we tried

Who’s got time for revolution between winning the bread, making the ends meet, looking after the kids and watching the latest season of Black Mirror on Netflix? No one.

This too is a feature of the capitalist world system; the most devious lock-in of them all. Capitalism has a monopoly on our existence, including our dreams.

Furthermore, to do what I am outrageously suggesting – to want less – assumes a certain kind of altruism towards an intangible and distant future. Even if we were good at dealing with things beyond the horizon (which we are not), won’t the next person in line just take our place in the consumption queue if we scale back and disengage even just a little bit? They probably will.

And still, and still – when you talk to your grandchild or nephew or niece in a decade or two, you can say that at least you weren’t fanning the flames on their world that we were burning.

Postscript

I have written this from a white western middle-class perspective as someone who in all likelihood belongs to the 1%. I have much more than I need and I am grateful for that. I am also very conscious that my current lifestyle is unsustainable.

If you want to help, please talk to your family, friends and colleagues about this. Once you’ve talked it over, search for and approach one of the movements in your local area, or start your own. We may still have a small window of opportunity to re-imagine our consumerist lifestyles for a better future.

Read, watch, participate

Movements and organisations

- Degrowth.info

- Research & Degrowth (R&D): An academic association dedicated to research, training, awareness raising and events organization around degrowth

- Simplicity Institute: Charter of Sufficiency

- Commoning, as discussed in David Bollier’s talk (2018): The Insurgent Power of the Commons in the War Against the Imagination

- Decolonisation

- Permaculture

Books

- Raj Patel and Jason W. Moore (2018): A History of the World in Seven Cheap Things – A Guide to Capitalism, Nature, and the Future of the Planet

– Read the complete introduction (pdf) - John Thackara (2015): How to Thrive in the Next Economy: Designing Tomorrow’s World Today

- Arturo Escobar (2018): Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds

Media

- A Simpler Way: Crisis as Opportunity (2016)

- Alan Storey (2017): Thoughts On White Privilege

- Godfrey Reggio (1982):Koyaanisqatsi

Articles

- Samuel Alexander (2014): Life in a ‘degrowth’ economy, and why you might actually enjoy it

- Ward, Chiveralls, Fioramonti, Sutton and Costanza (2017): The decoupling delusion: rethinking growth and sustainability

- Theodore Kaczynski (1995): Industrial Society and Its Future – I can’t endorse Kaczynski’s mission or methods; however, his criticism of technology was quite apt and prescient, especially for 1995

- Motherboard (2018): Scientists Warn the UN of Capitalism’s Imminent Demise

- Motherboard (2015): The End of Endless Growth: Part 1

- Motherboard (2015): The End of Endless Growth: Part 2

- Helsingin Sanomat (2018, in Finnish): Lasse Nordlund ei kuluta rahaa eikä sähköä – HS tutustui ”positiivisen Linkolan” elämäntapaan, jossa vessapaperina on rahkasammal ja kaikki tehdään itse

- Kate Crawford and Vladan Joler (2018): Anatomy of an AI System – The Amazon Echo as an anatomical map of human labor, data and planetary resources

Image sources

- Alexander Gerst on Twitter: ‘Just had a chance to take my first photos of dried-out Central Europe and Germany since a few weeks, and was shocked. What should have been green, is now all brown. Never seen it like this before.’

- Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992)

- Diagram by the author

- Karen Higgins (2013): Interdependence of Growth Loops

- MarketWatch: Want the American dream? Move to these countries instead…

- Helsingin Sanomat (2018, in Finnish): Lasse Nordlund ei kuluta rahaa eikä sähköä – HS tutustui ”positiivisen Linkolan” elämäntapaan, jossa vessapaperina on rahkasammal ja kaikki tehdään itse

- Polyp: Addicted to Growth

- Great Transition: The only sustainable growth is degrowth

- NASA: A World On Fire

All content copyright © Jussi Pasanen and respective owners, as referenced. This essay was originally written in August 2018 and published in October 2018. Thanks to everyone who reviewed versions of it.